by: Ronica Stromberg, NRT & EPSCoR Program Coordinator

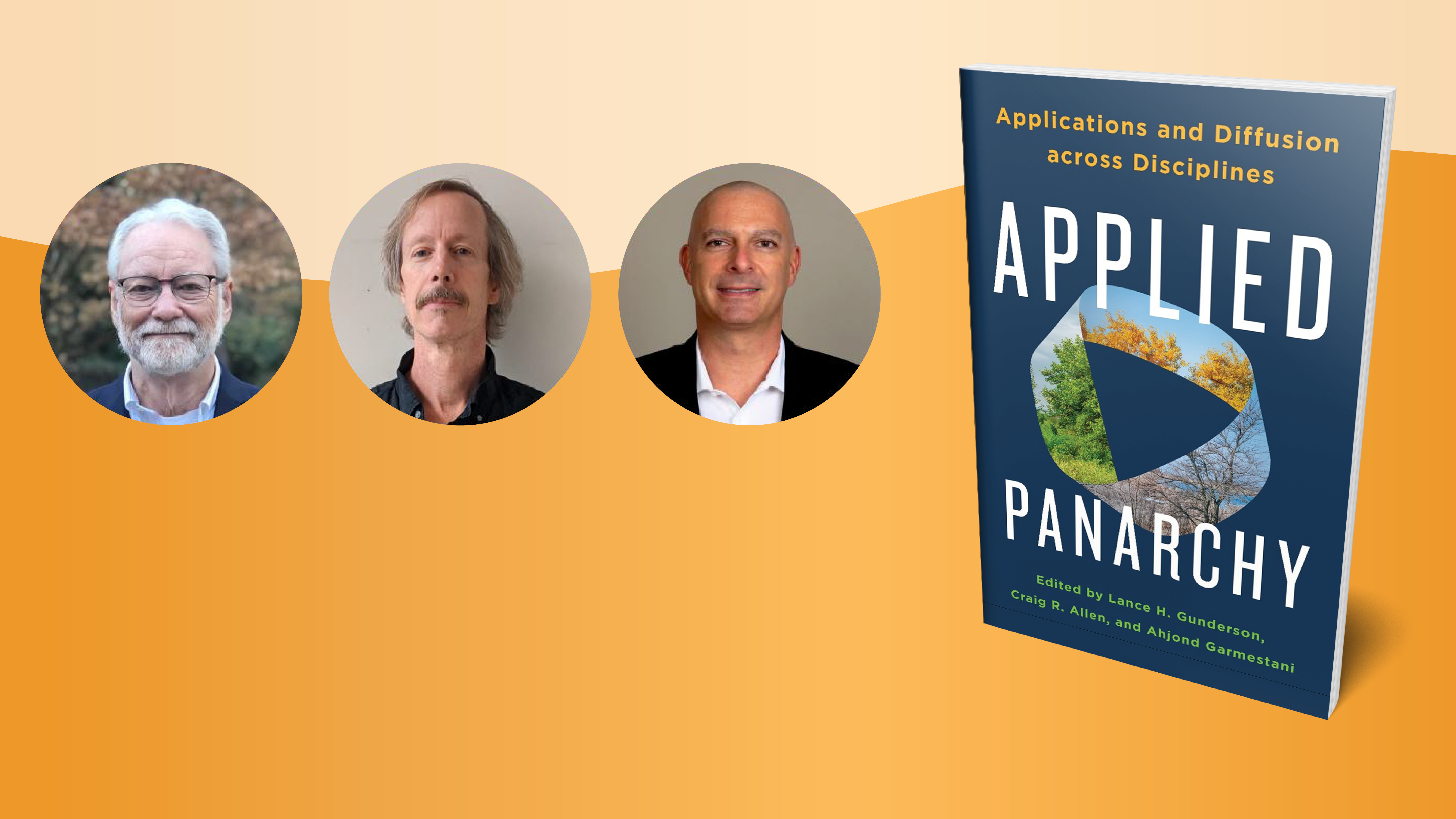

As a pioneer in the study of ecological resilience and panarchy theory, Craig Allen, the director of CRAWL, recently blazed those trails further by publishing the new book Applied Panarchy: Applications and Diffusion Across Disciplines.

In it, Allen and coeditors Lance Gunderson, ecology professor at Emory University, and Ahjond Garmestani, EPA scientist, updated readers on how panarchy theory has been refined and applied in various fields since being introduced 20 years ago.

Gunderson and C.S. “Buzz” Holling, the father of resilience theory in ecology, first laid out the panarchy concept in Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems.

“Panarchy is a theoretical model that helps us understand resilience in complex systems, how those systems hold up under disturbance,” Allen said. “The Panarchy book laid out big ideas. Our Applied Panarchy book follows up, putting those big ideas into practice and testing them and demonstrating utility to the management of social-ecological systems. It goes from theory to practice.”

Gunderson pointed out how panarchy theory differs from the traditional way of viewing the structure of ecological systems. Traditionally, scientists viewed ecological systems as having a hierarchical structure that didn’t change much and that had change in the system coming from variables at the top of the hierarchy, like climate or soil, and then filtering down through the system.

“What we found in ecosystems with a large degree of human intervention, though, was that the hierarchical view of ecosystems didn’t account for how small, fast things can interact to create change up the hierarchy,” Gunderson said.

He cited the COVID-19 virus, wildfires and the spread of red cedars in the Great Plains as examples of bottom-up processes that can occur in systems.

“It’s a combination of these top-down and bottom-up processes that generate non-linear and surprising system dynamics,” he said.

In Applied Panarchy, Gunderson, Allen and Garmestani compiled and edited the work of various authors who wrote about how resilience and panarchy concepts are being applied in various fields. In one case study presented, community leaders in Flint, Michigan, used panarchy theory to address problems with drinking water and malnourishment and move toward a more sustainable food system.

Other authors wrote about the use of panarchy theory in law, economics, geography and social science and how the theory has been modified based on those uses.

“I think the second major point of the book is that these ideas from systems ecologists have been adopted by scholars in other disciplines, especially those who recognized that assumptions about system behaviors that center on equilibria and non-stationarity are no longer valid,” Gunderson said.

Allen has spent much of his career identifying and trying to quantify cross-scale structures and dynamics, such as the transition from grassland to woodland in both geographical space and in time.

He said the greater access to data and computing technologies in the past 20 years has allowed scientists to track changes on the landscape and see the direction that changes are headed and at what speed. If they can communicate those changes to landowners, that opens the possibility of intervening sooner in harmful changes in land and preventing those from occurring in other areas.

Gunderson said that since the first book on panarchy was published, more researchers are looking at systems as integrated or coupled.

“They're not just ecosystems that humans intervene in,” he said. “With a lot of studies, researchers just focus on, ‘Well, the environment is out there, but really what's important are all of the human dynamics that involve how people organize or how people understand and communicate that understanding.’”

The newer approach to studying problems in complex systems crosses disciplines and integrates scientific understandings and approaches, he said.

Panarchy theory can be applied across disciplines but has not affected disciplines so much as individuals doing integrated systems work, Gunderson said.

“It’s almost a new kind of hybrid social-ecological scientist like Ahjond Garmestani, who has training in both natural and social sciences,” he said.

Allen said that although panarchy theory is still somewhat novel, it is rapidly spreading, similarly to how related resilience theories spread over the past 50 years.

“If you look at citation rates and do keyword searches in Google for ‘panarchy,’ it's going up, up, up, which is nice to see,” Allen said. “People are using the theory and applying it to their systems and advancing the scientific body.”

He and Gunderson said they wanted to publish Applied Panarchy book as an homage to Holling, who advised Gunderson on his doctoral degree and worked with both Gunderson and Allen in their postdoctoral research.

“He passed away about two-and-a-half years ago now, and a lot of the reason behind publishing this book was as an homage to Buzz, to show his creative and amazing ideas are still being used and applied,” Gunderson said. “We dedicated the book to him. Buzz was someone who really changed the way that we think about and manage complex resource systems.”

Allen said he hopes that panarchy ideas take off and spread the way resilience ideas did but he will be fine with it if the ideas are ultimately proven wrong.

“That’s how we advance science and people build on it,” he said.

Gunderson agreed, saying he hopes that publishing Applied Panarchy provides the framework for the next generation of scholars to reject.

“That’s really what the hope is, that they use this as a way of testing and generating new ideas and concepts and replacing it with some of their own,” he said. Applied Panarchy: Applications and Diffusion Across Disciplines is available for preorder through Amazon at $9 for paperbacks and $46.55 for the Kindle version.